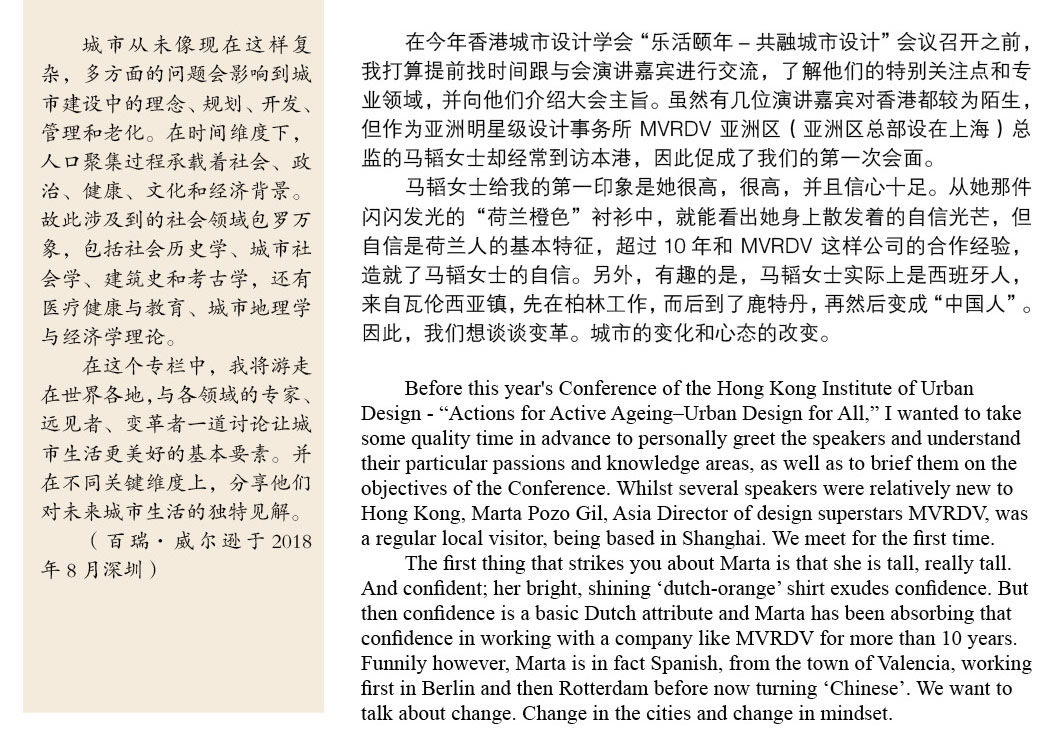

人与街道

我们首先讨论的是,马韬女士和我所熟知的欧洲城市设计原则,是否能真正成功地应用在中国?毕竟许多城市都是在鲜有科学数据收集或深入分析的概念基础上进行改造和发展的,而仅仅是基于设计师提供的海外参照图例。 “亚洲的社会元素是不一样的” 马韬女士对此总结道。在荷兰,社会参加与社会支持很普遍。而中国则更加依赖家庭关系来实现社会融合和相互关照。“譬如,当我们为老年人设计时,重要的是要超越城市标准的设计原则(在很多情况下是指技术解决方案),并且关注社会关系以及如何在更广阔的空间发展。”逐渐的,我们——建筑师、城市规划师和设计师——可以通过我们的工作改变人们的思维方式。从这个意义上说,项目可以成为一个模范,它能够塑造用户的思维方式和行为,甚至有希望重塑社会。这既有巨大的潜力,也有重大的责任。”

在世界上荷兰人一直是道路开发的创新者与改革者。荷兰的自行车数量超过其居民人数,在阿姆斯特丹和海牙等城市,由自行车完成的旅程比例高达 70%。同今天的中国一样,在 20 世纪 50 年代和 60 年代,随着荷兰的汽车保有量飙升,道路变得越来越拥挤,骑行者因而无路可走。同样汽车数量的增加导致了死亡人口的大幅增加。作为回应,兴起了“Stop de Kindermoord”(阻止儿童谋杀)的社会运动,要求为儿童提供更安全的骑行环境。 1970 年代的石油危机进一步给荷兰政府造成了压力,从而限制其城镇的机动车辆发展,并对骑行基础设施的优化和其他交通工具进行投资,使荷兰的街道更安全,城镇更人性化、更宜居。

荷兰的城市规划者巧妙地改变了其西部城市化进程中以汽车为中心的道路建设政策。在许多城市中,自行车道与机动交通带是完全隔离的。而有时,在空间不足且两者须共享车道的情况下,通常可以看到一个标志,上面展示着一个骑自行车的人,和后面跟着一辆汽车的形象,旁边还写着“自行车道:汽车为客”。在交叉路口也一样,骑行者们拥有优先权,汽车(几乎总是)耐心地等待你通过,这背后的观点是“自行车是正确的”。

“有绿地的安全道路”(生活院子)的发展在整个 70 年代和 80 年代被广泛应用,并且仍然盛行。在法律上和官方上都是优先考虑街道的生活功能,如步行、聊天、玩耍等,街道的生活功能远比交通功能重要,街道的广阔空间用于步行及玩耍。车速在“有绿地的安全道路”上被限制为“步行速度”,15 公里/小时,停车也受到限制。

荷兰道路工程师汉斯•蒙德曼(Hans Monderman)开创了“共享空间”(Shared Space)方法,这是一种将道路使用者模式之间的隔离最小化的城市设计方法,已广泛运用于荷兰的街道。这是通过去除诸如路肩、路面标志、交通标志和交通灯等特征来实现的。在不清楚谁具有优先权的情况下,驾驶员会减速行驶,进而降低车辆的主导地位,减少道路伤亡率,并提升其他道路使用者的安全。

PEOPLE AND STREETS

We first wonder if the European urban design principles that Marta and I are familiar with can actually translate successfully into China? Afterall many cities are being transformed and developed on concepts with little scientific data collection or deep analysis, but rather are based on the look of the designer’s overseas reference photographs. “The social component is different in Asia” suggests Marta. In the Netherlands, participation and social support is the normal, society is primarily 'civic minded', contrastingly, China is more heavily reliant on family networks for social inclusion and care of each other. “For instance, when it comes to design for the elderly, it is important to go beyond the standard urban design principles, which in many cases are technical solutions, and focus on the societal relations and how they can be developed in a wider way." Step by step, Architects, urban planners and designers in general, can together change people’s mindset through our work. In this sense, the whole project can become a model that can shape the mindset and behaviour of the users and hopefully a wider society. This has tremendous potential but also big responsibility.”

The Dutch have been world innovators in street development and a ‘changing mindset’. There are more bicycles than residents in The Netherlands and in cities like Amsterdam and The Hague up to 70% of all journeys are made by bike. In the 1950’s and 1960’s, as car ownership rocketed, and much as in China today roads became increasingly congested, cyclists were squeezed off the road. The jump in car numbers caused a huge rise in the number of deaths. In response a social movement arose ‘Stop de Kindermoord’ (Stop the Child Murder), demanding safer cycling conditions for children. The oil crisis of the 1970’s put further pressure on the Dutch government to restrict motor vehicles in its towns and cities and to invest in improved cycling infrastructure and other forms of transport that would make Dutch streets safer, and towns and cities more people-friendly and liveable.

Dutch urban planners smartly diverged from the car-centric road-building policies being pursued throughout the urbanising West. In many cities, cycle paths are completely segregated from motorised traffic. Sometimes, where space is scant and both must share, there are street signs showing an image of a cyclist with a car behind accompanied by the words 'Bike Street: Cars are guests'. At junctions too, it is those using pedal power who have priority, where cars (almost always) wait patiently for you to pass, the idea being that "the bike is right".

The development of ‘Woonerf’ (living yard), abundantly applied throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s and still prevalent, legally and officially prioritises the living functions of the street - walking, talking, playing, over and above the traffic function, using the full width of the street space to walk and play. Traffic in a ‘woonerf’ is restricted to "walking pace", at 15 km/h and parking is also restricted.

Streets were adapted further with the work of Dutch traffic engineer Hans Monderman, who pioneered the ‘Shared Space’ method, an urban design approach that minimizes the segregation between modes of road user. This is done by removing features such as kerbs, road surface markings, traffic signs, and traffic lights, making it unclear who has priority, drivers will reduce their speed, in turn reducing the dominance of vehicles, reducing road casualty rates, and improving safety for other road users.

过程

马韬解释说,以不同的方式做事意味着更多的努力和额外的研究工作,不仅需要证明创新方案的可行性,更需要说服业主和政府。然而,只有挑战现状才能取得进展。在中国,人们非常愿意尝试新的方法,而不是像典型的西方文化那样抵制变革。然而,“不同地区的政策、社会行为和支持系统是不一样的,只是简单地复制或嫁接海外解决方案是行不通的”,马韬女士说道。“本地问题需要本地解决方案,引进不同背景的智库专家对于生成新的视角和从不同的角度看事物至关重要。只有这样,改变才能真正的到来。再次强调,重要的还有这个过程”。

啊,是这个过程,但究竟这个过程的关键是什么呢? “所有各方都需要明白,项目无论如何都会被本地化调整。(项目)总是会有不同的本地特色(生活方式、需求、审美),即使你试图完全效仿海外的例子,也会有法规、法律、体系和指引来调整项目,使其本地化。这个过程塑造了结果。

一个项目必须针对使用它的人确定的需求来进行。因此,至关重要的是尽早让所有利益相关者参与到项目中来,包括城市周边地区的利益相关者,而不仅仅停留在物理概念上的利益相关者。成功不能以其所使用的材料的质量、外观或遵守技术指导方针或等级来判断。交付的方案必须是“相关的”,而不仅仅是设计者、政府或官员的猜测或直觉。项目必须让终端用户能够切实使用。在荷兰,是“社团”而非“政府”,是社区的管理者,这从根本上改变了项目的最终用途目标。“当然,我们也必须以密度为导向。如果有更多的集中,结果会产生更多的共鸣。”

THE PROCESS

Marta explains how doing things differently implies extended effort, research and detailed work to demonstrate to the client and government than an ‘innovative plan’ can work. Nevertheless progress only comes by challenging the status quo. In China there is a strong willingness to try new approaches rather than the resistance to change that is typical of western culture. However, “where policies, social behaviour and support systems are different, just copying or transferring overseas solutions can’t work” says Marta. “There need to be local solutions to local problems, but bringing in thinkers from different backgrounds is crucial to generate new perspectives and to view things through a different lens. Only then, can change truly come. Again, it’s the process that’s important.”

Ah, the process, but what is the key to this process exactly? “There needs to be an understanding from all parties that the project will be adapted regardless. There are always local ingredients of lifestyle, needs, and aesthetics, that are different and even if you try to strictly follow an overseas example there are codes, laws, systems and guidelines that will adjust the project and localise it. The process shapes the outcome.

A project must address the identified needs of the people who will use it. It’s essential therefore to engage all the stakeholders early in a project, including the urban neighbourhood, and not just carry out physical mapping alone. Success can’t be judged on the quality of the materials used, the way it looks or compliance with technical guidelines or ratings. The programs delivered must be ‘relevant’, not just be the guesses or instincts of the designer, government or officials; the project must function primarily for the end users. In The Netherlands it’s the ‘community’ that are primarily the neighbourhood managers and not the ‘government’, which fundamentally alters the end use objectives of a project. “We must also be guided by density however, where there is more concentration, outcomes resonate more.”

变化即将到来

在我们的讨论中,马韬女士对很多事情都“着迷”,但最“着迷”的是变化。“看到在同一时间、同一地点同时发生的各种各样的事情,实在令人着迷。“科技和能源供应将很快改变整个城市的结构和人们的生活方式。例如,在上个世纪,城市都是围绕汽车而设计的。随着交通和城市基础设施的发展,我们对城市的体验将发生巨大的变化。现在已经出现了这样的情况:大城市的大片区域被交还给居民,汽车也被禁止。与此同时,新的想法正在被测试:地下超音速运输、城市空中交通和新的拼车应用。我们在高速发展,变化就在我们身边。"

马韬女士表示:“已建成的环境对人们的日常生活影响甚大,甚至比其他人的影响都大。”她觉得大数据分析是促进和加速城市变革的一项重要技术。通过收集、整理和分析大量数据,我们将能够准确地了解人们如何利用城市以及他们希望如何使用城市,因此我们可以从个人和集体层面为我们的社区提供更好的解决方案。

然而,为了创造积极的变化,大数据带来了巨大的挑战。 “在任何变化中总会有人抱怨,因为这需要人们停止做熟悉的事情,开始做新的事情。人们需要时间来适应。但是人类的适应性非常强,很快他们就会忘记以前的情况。有时候,非常简单的改变就能让社会变得更好”

这个讨论促使我们思考到中国的发展模式是如何不是像西方那样线性的,而是更加互动式或循环式的。每一个项目都是一个试点项目,在第一阶段,通过在“试验台”实时学习改进提升。没有时间去仔细计划太多细节,改变的步伐总是太快;花太多时间思考则原有基线已变,市场机遇已逝。“速度很好,”马韬女士认为。“它促进变革,改变通常是好事。更重要的是,好的变革促进了下一步更好的变化。然而,速度确实会影响人们,使他们处于压力之下,使他们紧张和不可靠。速度的压力会导致混乱,从而导致沟通不畅。然后,就不能满足预期的质量要求了。问题的出现并非来自于速度,而是来自于沟通不畅。”所以高速可以造就突飞猛进的学习,但也会造成沟通不畅,这就是我们中国的现状。

CHANGE IS COMING

Marta is ‘fascinated’ by many things during our discussion but ‘change’ is the main one. “It’s fascinating to see the multiplicity of things that are happening all at the same time, together, in the same place.” “Technology and energy supply will soon change the whole fabric of the city and the way people are going to live. For instance, last century, cities have been designed around the car. As mobility and urban infrastructure develops, there will be massive transitions coming in how we experience the city. It is already happening that larger areas of major cities are being given back to the people and cars are banned. At the same time new ideas are under test: underground hypersonic transportation; urban air transportation; and new ridesharing apps. We are moving forward at high speed and change is all around us.”

“The built environment has a huge influence on how people act out their daily lives, more-so even than the influence of other people,” thinks Marta. One important technology that will facilitate and accelerate change in our cities is big data analytics. With the ability to collect, organise and analyse large amounts of data, we will be able to come up with an accurate understanding on how people uses the city and how they would like to use it, and therefore we can think of better solutions for our communities, at individual and collective level. Nevertheless, big data comes with big challenges in order to create positive changes. “In any change there will always be people who complain, because it requires people to stop doing things that are familiar and start doing things that are new. People need time to adjust. But humans are incredibly adaptable and very soon they will have forgotten how things were before; sometimes just very simple changes can make a huge difference for the better.”

The discussion leads us to consider how China’s development mode is not linear, as in the west, but far more “iterative” or circular. Every project is a pilot project, a first phase, to be improved upon by being a test bed for real time learning. There is no time to plan too carefully and in too much detail, the pace of change is too fast; spend a long thinking and the baseline will have changed, the market will have already moved on. “Speed is good,” thinks Marta. “It promotes change, and change is generally a good thing. What’s more, good changes promote further better changes. However, speed definitely affects people, it puts them under pressure, makes them nervous and less reliable. The pressure of speed can lead to chaos and this to a breakdown in communication. Its then that the quality of expectations aren’t delivered. Problems don’t come from speed, problems come from poor communication.” So high speed can lead to fast learning, but also poor communication, and this is what we have in China.

包容性或边缘化?

马韬女士同样还“致力于”复杂性。“我们应当转向更社会化的生活,我们是社会化的动物,但目前一切都是以利益为导向、以绩效来衡量。我们必须把社会问题放在首位,并将社会问题与经济问题加以平衡。”她在不久前阅读了萨斯基娅·萨森教授的《驱逐:全球经济中的野蛮性与复杂性》一书,作者在该书中表达了她的关切与担忧:全球范围内加剧的收入不平等、流离失所的人群、加速的环境破坏,同时该书阐述了这些是如何被解读为一种驱逐,让人们从职业生涯、生存空间、甚至切实存在的数据中被“驱逐”的。“对经济数据做不出贡献的人似乎不再存在,只是他们被排除在未来规划和社会进步之外了。人们要么生来幸运,要么生来不幸。”

回看我们大会的关注重点,老年人似乎是一个经常被列入非生产性人口的群体,从而导致他们被“驱逐”。但是,没有人能逃脱年龄陷阱。在人口老龄化的情况下,没有人会洪福齐天,即便富人也不例外。我们每个人都与家中的老人有关,并且能够明白我们终有一天也将身处同样的境遇。我们最终一致同意,建设不将老年人排除在外的城市空间是至关重要的,而这亦将常态化。马韬女士笑着说:“我对此表示乐观。”

INCLUSIVITY OR MARGINALISATION?

Marta is also ‘devoted’ to complexity. “We need to move to more social living, we are social animals but at the moment everything is about profit and measured by performance. We have to put social issues to the front, and then balance them with those of economics.” She has just read professor Saskia Sassen’s ‘Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy’ and voices her concerns raised in the book of globally soaring income inequality, displaced populations and accelerating environmental destruction. The book presents how these can be understood as a type of ‘expulsion’ of people from professional livelihood, from living space, even from the very data of existence. “People not contributing to economic data no longer seem to really exist and are excluded from planning and progress. People are either born lucky or not lucky.”

Coming back to the focus of the Conference therefore it seems that the elderly are a group that have all too often been included in the non-productive demographic, leading them to be “expulsed”. However, nobody can escape the age trap; nobody gets lucky in an ageing population, not even the wealthy. Everyone can relate to the elderly in their family, and can understand that they themselves will be in the same position one day. We therefore finish in agreeing that the importance of building inclusive city spaces that don’t marginalize the elderly will be increasingly normalised. “In that sense I’m positive” smiles Pozo.